The Himba people are indigenous, semi-nomadic people who mostly reside in the Kunene Region of northern Namibia. The tribe has an estimated population of around 50,000 and mostly subsists on livestock farming, particularly breeding sheep and goats, though they also grow crops like millet and maize.  These herders live very simple lives, far different from the modern lifestyles of those who live in urban cities. The tribe is comprised of smaller family communities and members of these family villages dwell in circular, wooden huts which were built to surround an “okuruwo†– a sacred fire the Himba people believe allows them to connect with the spirits of their ancestors. These homesteads also have specially-built enclosures they refer to as “kraal†in which they rear the cattle.

What really makes the Himba people of Namibia so distinctive from the perspective of Westerners is their appearance. They are known for covering their skin with red ochre pigment, which is a mixture of clay, sand and ferric oxide. But another special thing that really sets them apart from the rest of the world is the way they see and perceive things.

Even when looking at the same object, people can see things very differently. In the case of the Himba people of Namibia, this truth applies not only figuratively but literally as well. And not only do they see things differently from most humans, they seem to do it better, too, as research shows that they can focus on details better and are also less susceptible to visual distractions.

Modernization as a Factor that Alters Vision and Perception

This interesting finding compels us to ask this question: How is this possible? If we are all generally born with the same organs needed for seeing and perceiving, shouldn’t a traditional community like the Himba people see or perceive our surroundings no better than the rest of us do?

According to scientists, the answer lies in the theory that vision and perception are not solely a matter of biology and neurology. This means that they can also be influenced by external factors such as environment and culture. And in the case of the Himba people, these semi-nomadic people see and perceive the way they do because their minds have not been altered by modernization, which the likes of Jules Davidoff, a psychologist and professor at Goldsmiths, University of London, believes have significantly affected the visual focus and attention of those who belong to modern, urban societies. Â

Jules Davidoff’s Experiments on The Himba People

Davidoff conducted several studies and experiments on vision, perception, and attention with the Himba people as his main subjects, and the results of his research supported the supposition of several other scientists that modernization has changed the way we see, perceive and pay attention to the things we look at. That is why the people belonging to a traditional culture like that of the Himba people are less likely to commit errors in their perception of size and distance and are also less susceptible to getting distracted from their concentration.

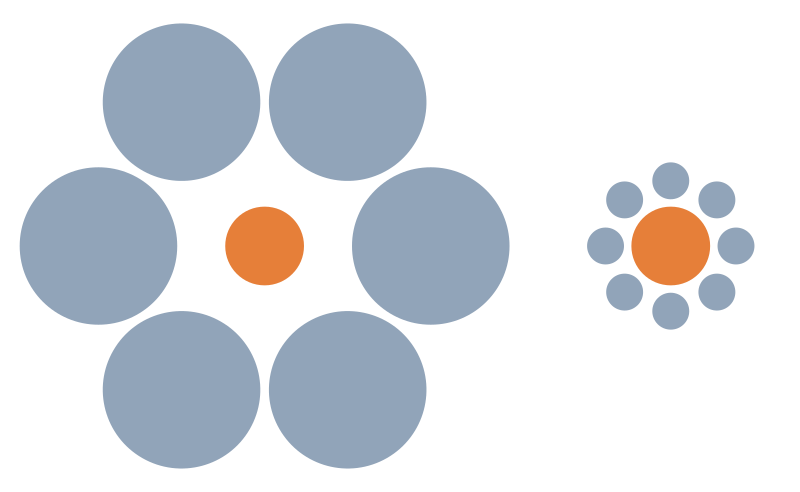

Many of Davidoff’s earlier experiments involving the Himba people utilized the famous Ebbinghaus Illusion. Also known as the Titchener circles, this optical illusion is one that concerns size perception, and it was first developed by renowned German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus before its use was popularized by British experimental psychologist Edward Titchener.

The most famous version of this optical illusion features two circles of the same size placed in proximity of each other in order to be compared by the subject looking at them. However, the first circle is surrounded by circles much larger than its size while the second circle is surrounded by smaller ones. The positions of all the circles involved are supposed to make it appear that the main circle encircled by larger circles is smaller than the central circle contained by the small circles.

For most Westerners, the optical illusion succeeded in tricking them that the first central circle is smaller than the latter. However, when Davidoff showed the images to members of the Himba people, they weren’t as likely to fall for the same trick. According to an article he published with his colleagues in the Journal of Experimental Psychology in 2007, the illusion had a weak effect on the Himba people because of their bias towards local processing. This meant that when presented with an image featuring multiple objects, they have the tendency to focus on the smaller details – which in the case of the Ebbinghaus Illusion was the main circles – instead of the complete picture. And because they ignored the context of what they saw – which was the image of two circles surrounded by large and small circles, respectively – the illusion failed to distort their perception.

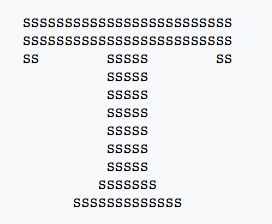

Davidoff and his colleagues went on to test the Himba people’s local bias on focusing on fine details by asking his subjects to compare Navon figures. A Navon figure is used to compare local and global processing biases across race and culture. It features a large and recognizable shape or letter that is made of repeat copies of a different and much smaller shape or letter. For example, a Navon figure could be a large letter T made up of copies of the letter S. In this case, the letter T is the global feature while the S is the local one.

The result of the study, which was first published in 2013, revealed that the subjects from the Himba people of Namibia have the tendency to focus on smaller details over the larger and overall image, which confirms that they are biased towards local processing. However, despite this perceptual bias, the Himba people are more flexible and have more control over their selective attention. This means that while they tend to notice the small details first, they can just as easily see the “big picture†if they are asked to do so.

Further experiments showed not only the Himba people’s perceptual bias for the small details and their flexible selective attention but also a reduced distractibility. Compared to Westerners living in urban cities, the members of a remote culture such as the Himba are less affected by visual distractions. They can identify their target object better than others even when other moving objects are present to disrupt their focus.

A possible explanation for why the Himba people can “see†and focus better than everyone else is their traditional and simple lifestyle. As herders, part of their everyday life is to identify cattle. To be able to individuate dozens of animals, they had to train their eyes to quickly spot distinctive features and markings on their sheep and goats from a distance. This is a special ability that usually only traditional herders like the Himba can develop, and not something people from modern societies can easily teach themselves to do, especially since our modern lifestyle is supposedly the very thing that gets us so easily distracted and makes us less attentive to detail.

Conclusion

Those of us who reside in urban environments live in a fast-paced and cluttered world where a lot of things happen all at once. We encounter countless buildings, cars, and people on a daily basis. Not only that, we usually don’t just do one thing at a time. We almost always have to multi-task, and because there are so many elements in our surroundings we have to watch out for, it becomes necessary for our attention to be always divided.

We may have once been able to see, perceive and pay attention to things as well as the Himba people in our distant past, but the demands of the modern world we live in today have made such gifts a luxury we simply can no longer afford.

—

SOURCES:

- http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20170306-the-astonishing-focus-of-namibias-nomads?ocid=twfut?source=Snapzu

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ebbinghaus_illusion

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Navon_figure

- http://research.gold.ac.uk/422/1/davidoff-judgements-ebbinghaus-illusion.pdf

- http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0956797612452569

- http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0026337

Leave your comments